Science

Physicists Unlock Structure of Radium Monofluoride Using Electrons

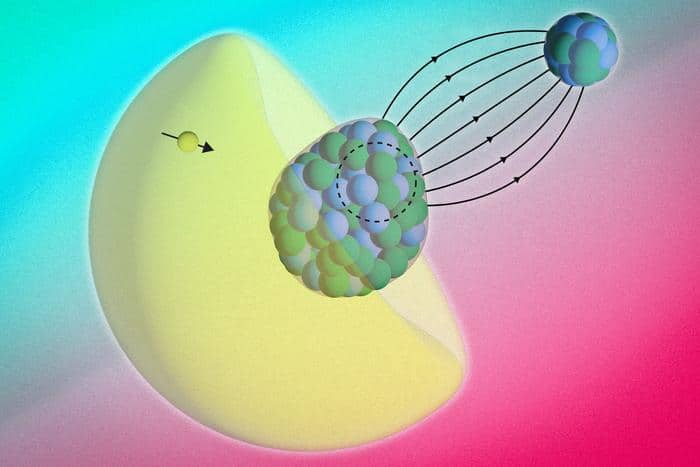

Physicists have achieved a significant breakthrough by obtaining the first detailed image of the internal structure of radium monofluoride (RaF). The study, which includes contributions from researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and other institutions, utilized the molecule’s own electrons to penetrate its nucleus and interact with its protons and neutrons. This phenomenon, known as the Bohr-Weisskopf effect, has now been observed in a molecule for the first time.

Shane Wilkins, co-leader of the study, emphasized the importance of these measurements for future research. They represent a crucial step towards testing for nuclear symmetry violation, a concept that may help explain why the universe contains significantly more matter than antimatter. RaF contains the radioactive isotope 225 Ra, which poses challenges for production and measurement due to its limited availability.

The process of creating 225 Ra requires a large accelerator facility to operate at high temperatures and velocities, yielding only minute quantities—less than a nanogram—over a brief period, as it has a nuclear half-life of around 15 days. “This imposes significant challenges compared to the study of stable molecules,” Wilkins noted. The research team needed extremely selective and sensitive techniques to elucidate the structure of molecules containing 225 Ra.

Choosing RaF for their study was strategic. Theoretical predictions indicated that this molecule is particularly sensitive to small nuclear effects that could break nature’s symmetries. Silviu-Marian Udrescu, the study’s other co-leader, explained, “Unlike most atomic nuclei, the radium atom’s nucleus is octupole deformed, which essentially means it has a pear shape.” This unique characteristic enhances the molecule’s ability to reveal vital information about nuclear structure.

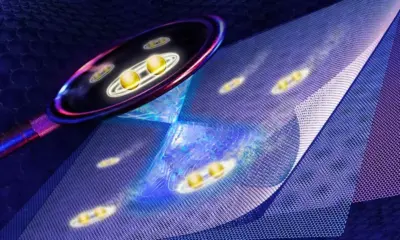

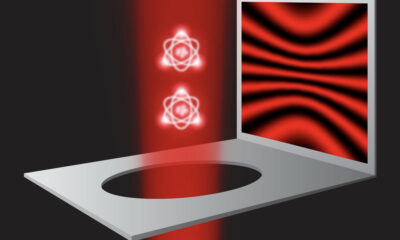

The research, published in the journal Science, focused on RaF’s hyperfine structure, which emerges from interactions between nuclear and electron spins. Investigating this structure can yield insights regarding the distribution of protons and neutrons within the nucleus. Typically, physicists treat electron-nucleus interactions as occurring over relatively long distances. However, in the case of RaF, that is not applicable.

Udrescu described the electrons in the radium atom as being “squeezed” within the molecule, which heightens the likelihood of their interaction with the radium nucleus. This behavior results in subtle shifts in the energy levels of the radium atom’s electrons. The team’s precision measurements, combined with advanced molecular structure calculations, confirmed the expected outcomes. “We see a clear breakdown of the long-range interactions picture because the electrons spend a significant amount of time within the nucleus itself,” Wilkins explained. “The electrons thus act as highly sensitive probes to study phenomena inside the nucleus.”

The implications of this work extend beyond the immediate findings. Udrescu stated that the study “lays the foundations for future experiments that use this molecule to investigate nuclear symmetry violation and test the validity of theories that go beyond the Standard Model of particle physics.” According to the Standard Model, each matter particle, from baryons like protons to leptons such as electrons, should have a corresponding antiparticle that is identical except for its charge and magnetic properties.

Despite these theoretical foundations, the Standard Model suggests that the Big Bang should have produced equal amounts of matter and antimatter. Yet, current observations reveal a universe predominantly composed of matter. The subtle differences between matter particles and their antimatter counterparts may explain this asymmetry. By searching for these differences, physicists aim to address the longstanding question of why matter prevails.

Wilkins believes that their findings will play a crucial role in future searches for nuclear symmetry violations using species like RaF. Currently, he is working at Michigan State University’s Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB), where he is developing a new setup to cool and slow beams of radioactive molecules. This advancement aims to facilitate higher-precision spectroscopy of molecules relevant to nuclear structure, fundamental symmetries, and astrophysics.

His long-term goal, in collaboration with the RaX team—which includes researchers from MIT, Harvard University, and the California Institute of Technology—is to implement advanced laser-based techniques using radium-containing molecules. The innovative approaches may unlock further understanding of the fundamental questions surrounding the universe’s composition and the nature of matter and antimatter.

-

Entertainment3 months ago

Entertainment3 months agoAnn Ming Reflects on ITV’s ‘I Fought the Law’ Drama

-

Entertainment4 months ago

Entertainment4 months agoKate Garraway Sells £2 Million Home Amid Financial Struggles

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoKatie Price Faces New Health Concerns After Cancer Symptoms Resurface

-

Entertainment2 weeks ago

Entertainment2 weeks agoCoronation Street Fans React as Todd Faces Heartbreaking Choice

-

Entertainment3 months ago

Entertainment3 months agoCoronation Street’s Carl Webster Faces Trouble with New Affairs

-

World2 weeks ago

World2 weeks agoBailey Announces Heartbreaking Split from Rebecca After Reunion

-

Entertainment3 months ago

Entertainment3 months agoWhere is Tinder Swindler Simon Leviev? Latest Updates Revealed

-

Entertainment4 months ago

Entertainment4 months agoMarkiplier Addresses AI Controversy During Livestream Response

-

Science2 months ago

Science2 months agoBrian Cox Addresses Claims of Alien Probe in 3I/ATLAS Discovery

-

Health5 months ago

Health5 months agoCarol Vorderman Reflects on Health Scare and Family Support

-

Entertainment4 months ago

Entertainment4 months agoKim Cattrall Posts Cryptic Message After HBO’s Sequel Cancellation

-

Entertainment3 months ago

Entertainment3 months agoOlivia Attwood Opens Up About Fallout with Former Best Friend